Do You PIREP? Here’s Why You Should

Recent NTSB forum highlights the reporting tool’s promise, pitfalls, and the need for more of them.

By Christopher Freeze, Senior Aviation Technical Writer

Pilot reports, better known as PIREPs, are the only source of pilot-observed weather aloft and are one of the best sources of wildlife hazard information. Unfortunately, in recent years pilots haven’t been issuing PIREPs as often as in the past. And while technological advancements that automatically transmit important weather data have filled some of the informational gap, some of the PIREPs that are reported—a practice that ALPA strongly recommends and encourages pilots to do—aren’t getting out to pilots who would benefit from them.

PIREPs—the original “crowd sourcing”

“There’s an old saying, ‘everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it,’” said Robert Sumwalt, an NTSB member, during a forum about PIREPs the agency hosted in Washington, D.C., in late June. “The one thing we can do about it is report it, and make sure that every report about the weather is available to those who need it most. But too often we don’t.”

Sumwalt, a former ALPA member and recipient of the Association’s 2004 Air Safety Award, became convinced of the need for additional focus on PIREPs after reviewing accident data, speaking with investigators, and reflecting on his 30-plus years in aviation—including his experience serving on the ALPA aviation weather committee. He acknowledged, “We at the NTSB have investigated numerous accidents that illustrate a complex set of relationships in the PIREP system as it presently functions—or doesn’t function,” noting that, “How often is loss of control linked to flying VFR into IMC, or encountering icing conditions without the pilot knowing others had encountered those same conditions just moments before?”

PIREPs are one of the major ways that National Weather Service (NWS) forecasters can verify their upper-air forecasts as well as fill gaps in ground-station coverage. As with other safety programs, the NWS can only improve the system when it has accurate information—and reporting from pilots is key. The more frequently pilots provide accurate inflight information, the more NWS can learn about unexpected conditions and, more importantly, refine its forecast models.

“The reality is,” Sumwalt remarked, “only a fraction of the observed knowledge about weather hazards gets reported through the present system to the next pilot who needs the information. Think about that in the context of all the lives we lose each year in weather-related accidents.” Presently, the World Meteorological Organization estimates that less than 5 percent of weather information comes from PIREPs. And that number has been declining in recent years.

Begin with training

Speaking on the forum’s panel that focused on training, education, and operations, Capt. Steve Jangelis (Delta), ALPA’s Aviation Safety vice chairman and chairman of the Airport and Ground Environment Group, gave a line-pilot perspective as to when pilots use PIREPs and what they do with the data, and the importance of their accuracy. “PIREPs are not really part of our training program,” Jangelis stated. “As I started to go through some of our training syllabi, I noticed that one of our training scenarios involving wind shear shows a completed status, once you make a PIREP. So as you get through the wind shear and recover, the [scenario] is not completed until you make that PIREP to the simulator instructor. But as far as day-to-day PIREPs are concerned, issuing them isn’t in our training curriculum.”

When PIREPs are most valued

Based on his experience, Jangelis detailed the phases of a flight where PIREP information is sought. “During the takeoff and climb phase, probably the most important PIREPs we could receive [are related to] wind shear, turbulence, icing, or wildlife. If a pilot experiences icing in the climb, that is very important to us, and we want pilots to report that to air traffic control.

“During the enroute phase,” Jangelis continued, “we deal with turbulence, icing, and convective activity. We don’t reach out to a weather service to make that PIREP. We pass those observations on to air traffic control and our company dispatchers in hopes it makes it down through the proper channels toward a printed form or a weather briefing for another pilot.”

Discussing the importance of PIREPs in the final approach and landing, he noted, “Wind shear, turbulence, icing, and precipitation are all important factors to consider. PIREPs from preceding aircraft on approach help us understand what weather phenomenon we are likely to encounter while on approach.”

And while outside the scope of typical PIREPs, Jangelis addressed a critical item for pilots: “Braking action reports are very important. While they are subjective, they are important for pilots who are in sequence to land, as well as for pilots who are departing for their takeoff performance calculations.”

However, pilots aren’t providing as many PIREPs as in years past, and ATC isn’t asking for them. So what’s changed?

Lost in technology

Over the past decade, numerous technologically advanced systems have been generating automatic PIREPs—often without a pilot’s knowledge. Today, most atmospheric data collected by U.S. aircraft are transmitted automatically via the Meteorological Data Collection and Reporting System (MDCRS) to help develop upper air forecasts. Tropospheric Airborne Meteorological Data Reporting is another automated system that is designed to collect similar weather data from the atmosphere. The data are transmitted in real time to the operations center for analysis, distribution, and assimilation into high-resolution models.

On a daily basis, more than 140,000 wind and temperature observations are gathered via MDCRS, 100,000 of which are over the continental United States from more than 4,000 aircraft—including many from Alaska, Delta, FedEx Express, and United airlines (airplanes that Jazz Aviation pilots operate participate in the international Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay). And while these observations do help provide timely and accurate information to the NWS, there are no substitutes for line-pilot input highlighting a particular hazard in flight to fellow aviators, like low-level wind shear.

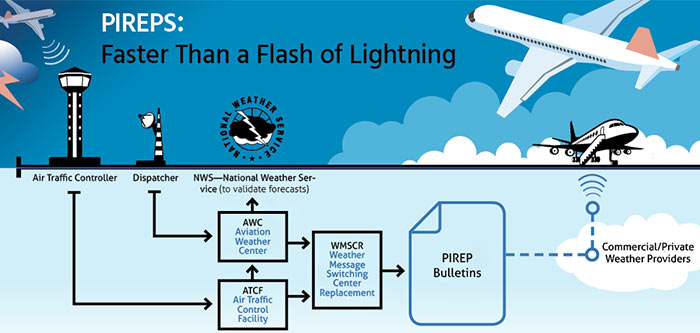

In addition, airlines occasionally communicate weather information internally via the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System that is sometimes not shared with others or the national system. Instead, it’s only sent to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Aviation Weather Center (AWC) for meteorological forecasts—but the AWC doesn’t circulate the PIREP information. If this information is shared externally, it will be transmitted to the Weather Message Switching Center Replacement, where it’s used to create PIREP bulletins for dissemination.

Talking about the positive aspects of automated weather reports, Jangelis acknowledged one of the trade-offs—the loss of conversation: “It works great, but we lose the shared information over the frequency. If you listen to any air traffic control tapes, it sounds very confusing to the layman. But our ears perk up when we hear reports of turbulence or icing, and we believe it’s very important that pilots pass it along.”

Jangelis cited an example of how conversation can engage and help fellow pilots: “Thunderstorms have been around forever—since the Wright Brothers were flying. But we use the radar to take a look at the weather, and the radio to ask whoever is on the frequency, ‘Hey, where is everybody going with this thunderstorm?’ ‘Well, they’re passing to the north’ or to the south.” Without PIREPs and discussion, ATC could assume the inflight conditions are acceptable.

In closing the forum, Jangelis acknowledged the event’s theme—“Weather for One Is Weather for None”—by saying that “Every flight I fly, PIREPs are issued.” Providing this weather information is one way pilots can all help each other, “And we’re encouraging it here at the Air Line Pilots Association.”

“That Time, When…”

In his opening remarks at a recent forum on PIREPs, NTSB member Robert Sumwalt recounted a moment early in his flying career: “A number of years ago, I was a 737 line check airman for my airline. I was giving initial operating experience to a new first officer. Because we were descending through clouds with a low temperature, we had engine anti-ice on, as we should. About seven miles from landing in Columbus, Ohio, I noticed that the first officer hadn’t set his airspeed bugs properly and was trying to get that sorted out. We broke out of the clouds around five miles out, and when I looked out to see the runway, I noticed we had clear ice on the windshield wiper bolt. I was surprised. I turned on the wing anti-ice system and reported the icing to the tower. More than the ice itself, their response surprised me: ‘Yeah, we’ve been getting those reports all morning.’”

Sumwalt rhetorically asked those in attendance at the forum, “Well, why wasn’t it reported to me?”

The Life of a PIREP: From Observation to Dissemination

Breaking down the process that makes a PIREP work, NTSB member Robert Sumwalt explained, “First, pilots have to voluntarily submit the PIREP. But as a pilot, I’ll admit that when we perceive the report isn’t going to get relayed to others, we tend to stop reporting. Then there’s the issue of accuracy: The PIREPs that are submitted often provide incorrect information, most commonly about time, location, and weather intensity. Once the PIREP is radioed in, it can be jotted down on a form—even though it’s 2016, a paper form—to be entered later into multiple systems that don’t communicate with each other. If all goes well and every party does his or her job, the update goes out to the national airspace system.”PIREPs: Faster Than a Flash of Lightning

From the moment pilots provide PIREPs to the dispatcher or to air traffic control, they become important reports that benefit the entire system. These observations can provide other pilots on the ground with the knowledge that can aid in their preflight planning and decision-making. Additionally, they give air traffic control personnel the information they need to inform more pilots in their airspace with timely, actionable information from a trusted source as to what to expect. Lastly, PIREPs give experts and computer models valuable data to enhance future weather forecast products.