Open Enrollment: Questions to Ask & Decisions to Make

By Marian Tashjian, Senior Benefits Specialist, ALPA Retirement & Insurance Department, and Kevin Cuddihy, Contributing Writer

While the exact dates differ, most airlines have their open enrollment for health insurance in the fall. Generally speaking, employees have a few weeks’ window every year when they can make any desired changes to their company health insurance coverage. While this article won’t give you a yes or no answer to the question “should I change?” it may help you evaluate your options and reach a decision. But before we explore how to determine if you should make any changes during this upcoming open-enrollment period, there are two important points to note.

At some airlines, you must reselect your health insurance coverage during open enrollment, even if you want to keep the same coverage. This is called active enrollment, as opposed to passive enrollment, where you continue with your current coverage unless changes are made. Flexible-spending account elections must be made each year even if your airline’s open enrollment is passive.

Pilots who experience what’s termed a “qualifying life event”—e.g., a birth, marriage, divorce, loss of job, just to name a few—can adjust their health insurance within 30 days following the event, no matter when it occurs.

Variables

There are four main monetary considerations involved in your decision: premiums, deductibles, copayments/coinsurance, and the out-of-pocket (OOP) limit. The premium is your monthly contribution toward the cost of your health plan. Most health plans generally require you to satisfy an annual deductible before any plan benefits are paid. For example, a plan with a deductible of $2,000 means that you’ll pay the first $2,000 of your covered medical expenses each year (although the deductible is waived for certain preventive-care services as mandated by law). Even while working through your deductible, you’ll still be eligible for any network discounts by your health-care administrator.

Once the annual deductible is satisfied, you pay the applicable coinsurance and copayments, if any, for all covered expenses until the total amount you’ve paid reaches the plan’s OOP limit, your maximum financial exposure under the plan. After the OOP limit is reached, all additional covered expenses you incur during the year are paid in full by the plan. Copayments (or “copays”) are a fixed amount you pay for things like office visits, prescriptions, or emergency room visits, while coinsurance is the percentage of the cost you’ll pay for covered services. For example, you might have a $20 copay for a visit to your primary physician, a $10 copay for a generic drug, or a $250 copay for a visit to an emergency room—or you might be required to pay 20 percent of the total cost instead, depending on how the plan is designed. Generally, the higher the deductible and your share of the coinsurance, the lower the cost of your plan and your premium contribution. Coinsurance amounts can also vary depending on if the doctor is in network or out of network, and you may be responsible for amounts over usual and customary charges when you go out of network.

Typical types of insurance

Your airline may not offer the full range of health plan options available, but chances are your selections include some of the following:

- Health maintenance organization (HMO)

- Preferred provider organization (PPO)

- PPO with a health reimbursement arrangement (HRA)

- PPO with a health savings account (HSA)

It’s important to understand that the underlying health plan is usually exactly the same for all the self-insured plan options made available by the employer. Most airline plans, with the exception of HMOs, are self-insured. In other words, each self-insured health plan option offered by your airline generally covers the same services. If one plan covers acupuncture, chiropractic care, and treatment for autism, for example, then all the self-insured plan options offered by your airline will likely cover these services. The only difference is your cost for each health plan option, including your monthly premium contribution, deductible, coinsurance, etc.

An HMO is a type of health insurance plan that usually limits coverage to care from doctors who work for or contract with the HMO. It generally won’t cover out-of-network care except in an emergency. An HMO may require that you to live or work in its service area to be eligible for coverage. A PPO, on the other hand, is a type of health plan in which you pay less if you use providers in the plan’s network. You can use doctors, hospitals, and providers outside of the network, but your out-of-pocket expenses for out-of-network care will be higher. Generally speaking, a PPO provides more flexibility in choosing your caregiver than an HMO.

Account-based high-deductible health plans

If you’re considering enrolling in a high-deductible health plan option, it’s important to understand the two types of accounts often associated with these plans—health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) and health savings accounts (HSAs). Both accounts are tax-preferred. This means contributions to, and distributions from, the accounts for otherwise unreimbursed eligible medical expenses aren’t included in income for federal (and most state) income taxes and federal employment (FICA) taxes. HSA contributions made directly to a financial institution and not via payroll deduction aren’t exempt from FICA taxes. Account balances may also grow tax-free if invested, though this generally applies only to HSAs, as HRAs for active employees are usually just notional accounts that aren’t invested and don’t accrue interest (as opposed to retiree-only HRAs, which are typically funded and held in trust).

HRAs and HSAs are very different in many respects. HSAs must be linked to a high-deductible health plan for HSA contributions to be permitted, while HRAs are often coupled with one but it’s not a requirement. Health plans with HSAs have government-mandated guidelines for minimum deductibles and maximum OOP expenses, while HRAs have no such government-mandated guidelines.

Funding and control under these two types of accounts also differ. HSAs may be funded by employers, employees, or both, and there are limits on the total amount that may be contributed. HRA plans must be funded solely by the employer, and there are no government-mandated limits. An HRA (for active employees) is typically a notional account controlled by the employer. Unused funds typically roll over from year to year, but the employee is usually not permitted to take unused funds if he or she changes to a different type of health plan or terminates employment. HSA funds, on the other hand, must be held in trust at a bank or other financial institution and always belong to the employee, who is free to use the funds for eligible out-of-pocket health-care expenses as they are incurred or to invest the balance and allow it to grow tax-free regardless of whether they later change to a different type of health plan.

As mentioned, health plans with HSAs have specific requirements with respect to minimum deductibles that must be satisfied before the plan pays any benefits. Except for expenses for preventive care and preventive prescriptions, an HSA-eligible plan can’t pay any expenses, including prescription drug expenses, until the applicable deductible is met. Most HRA plans cover prescriptions with a copayment or coinsurance, and the deductible applies only to other covered medical expenses. You should confirm how the HRA-based plan(s) offered by your airline work in this regard.

An often-misunderstood difference between HRA- and HSA-based health plans is how the deductible and OOP limits are applied when you elect coverage for one or more dependents. HRA-based plans generally operate like traditional PPO plans, where the single deductible applies to each individual when multiple family members are covered, and the family deductible is simply the maximum deductible that would apply to you and all your covered dependents collectively.

For example, in an HRA-based plan with a deductible of $1,500/single and $3,000/family, usually no one individual in the family would be required to satisfy more than a $1,500 deductible. However, the family deductible would be satisfied once the family’s collective expenses total $3,000. The same principle applies with respect to the OOP limit.

This is not the case with HSA-based plans. The minimum deductible of $1,350 (as of 2018) for single coverage applies to single coverage only. When the employee covers one or more dependents in an HSA-based plan, the minimum family deductible of $2,700 (as of 2018) must be satisfied, by one covered individual or collectively by all, before the plan may pay benefits other than for preventive care and preventive prescriptions. (Any embedded deductible in an HSA-based plan covering more than one individual must be at least $2,700). So any single member of a covered family must continue to pay the full cost of his or her health-care expenses until he or she, or the family collectively, spends at least $2,700 for covered expenses. This assumes the HSA-based health plan uses the minimum required deductibles; your HSA-based health plan option(s) may have higher deductibles.

Similarly, with respect to the OOP limit, though your plan may have embedded individual OOP limits, there is no government-mandated embedded single OOP limit when more than one individual is covered. Regardless, no individual in a family—even in an HSA-based plan—can be required to meet an OOP limit for in-network covered services that exceeds $7,350 (2018), the OOP limit under the Affordable Care Act.

For a more detailed chart on the differences between these two types of accounts, visit www.alpa.org/hsa-hra.

Making a decision

When reviewing health plan options during open enrollment, it’s typical to focus on the deductibles and OOP maximums. But you should also focus on the premium contribution required for each of these plans. While the higher deductible and OOP maximum often seen in high-deductible health plans may seem daunting, consider that many people won’t incur enough medical expenses during the year to meet the deductible, and most will never meet the OOP maximum—but every individual electing coverage will pay the annual premium. And as expected, the premium is highest for the plans with the lowest deductible.

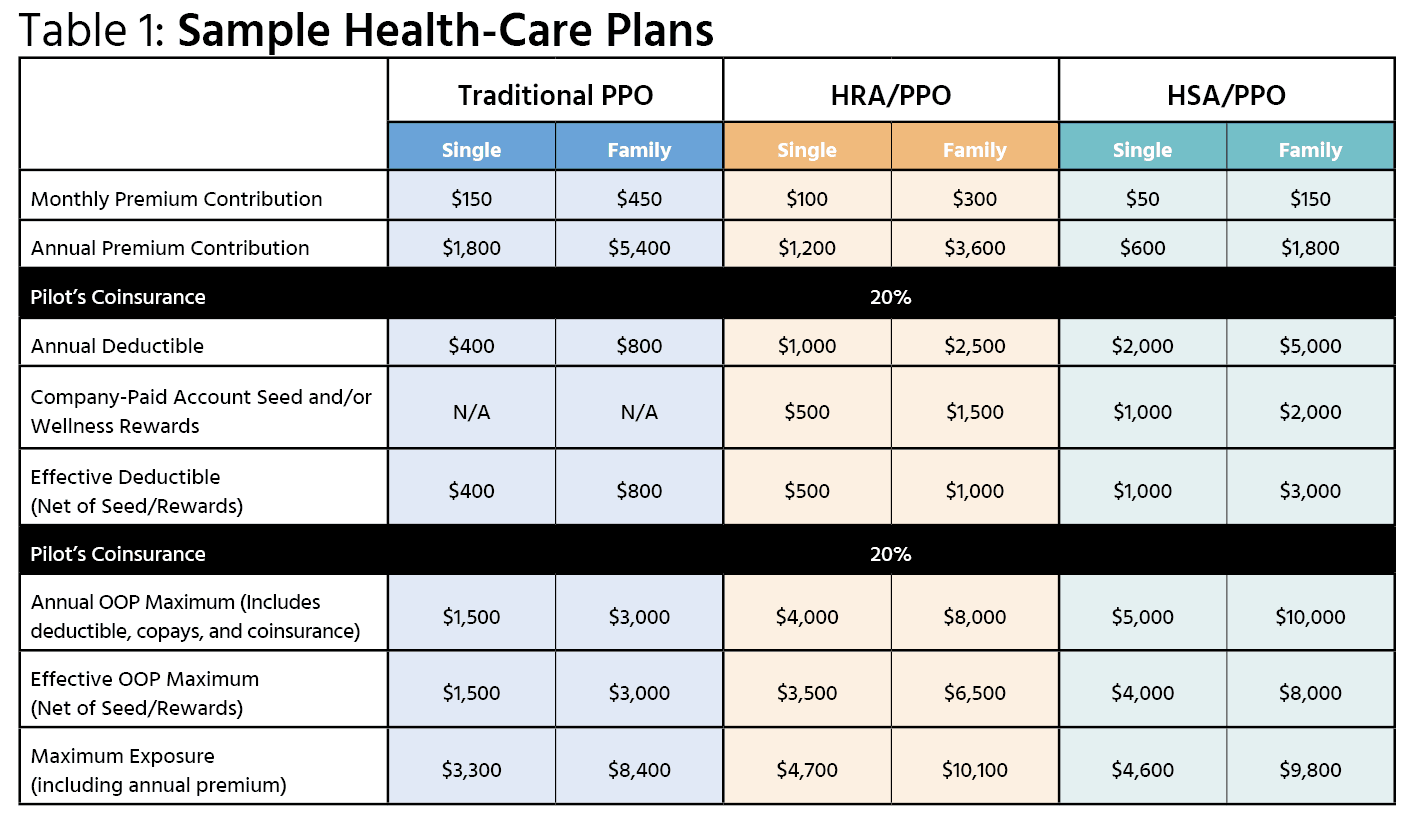

Consider the three sample plan designs illustrated in Table 1. A pilot electing single coverage with a $400 deductible under the traditional PPO will pay $1,800/year in premium even if he or she never uses any benefits that year. This pilot could choose to elect the HRA/PPO with the $1,000 deductible instead. The $500 HRA seed money the employer will contribute to reimburse the pilot’s OOP expenses reduces the deductible to $500 (the “effective deductible”). This is still $100 more than the $400 deductible under the traditional PPO, but the annual premium for single coverage under the HRA/PPO is $1,200—a $600 savings. If this pilot meets the deductible, he or she is no worse off; but if the pilot doesn’t, he or she is ahead of the game because of the $600 premium savings.

A pilot with family coverage considering these same options would pay $5,400 per year for coverage under the traditional PPO with an $800 family deductible or instead the pilot could consider family coverage under the HSA/PPO. After taking into account the employer’s HSA seed contribution, the effective family deductible under the HSA/PPO is $3,000. However, this pilot will only pay $1,800 per year in premium, a savings of $3,600 over the premium he or she would have to pay for the traditional PPO whether or not the family ever uses any benefits. The premium savings alone is more than the effective family deductible.

If you typically meet your deductible, you may want to do a similar analysis using the plan’s OOP maximums. Once again, take into consideration that the company-paid account seed and/or wellness rewards offset the OOP maximum (the “effective OOP maximum”). By adding each plan’s annual premium to the plan’s effective OOP maximum, you can determine the total maximum exposure for single and family coverage. In a worst-case scenario in which health-care expenses meet the plan’s annual OOP maximum, the maximum exposure for family coverage, including the annual premium, would be $8,400 under the PPO, $10,100 under the HRA/PPO, and $9,800 under the HSA/PPO. But if your expenses are lower, and you don’t meet the plan’s OOP maximum—you could be ahead of the game by choosing an account-based plan.

These are only examples intended to illustrate the factors you should consider. You should take into account your own circumstances and expected health plan utilization. And if you’re covering family members—especially young children—you’ll want to consider the habits of all family members on your plan. While wellness visits for children aren’t subject to the deductible (if the plan is not grandfathered under the Affordable Care Act), you’ll still need to account for anticipated treatment for each member of the family, not just you.

Summary

Now that you know more about the types of plans available and the variables included in the plans, you have the tools needed to determine whether you should change your current coverage. As you approach your open-enrollment period, take these three steps:

- Examine your current coverage.

- Research the options your company provides (contact your company’s HR Department for details, reach out to your master executive council R&I Committee, or e-mail R&I@alpa.org with your questions).

- Review the health-care spending for you and your family (if applicable) for the past few years.

Once you’ve done that, you should have enough information to begin plugging in the variables and determining which health plan is the best one for your coverage needs. And remember, there’s an open-enrollment period every year. If you change plans and find that it ends up being a wrong decision, you can always change back next year.

ALPA Insurance: Optional Plans for Members

One final variable to consider is that ALPA offers supplemental insurance to all members in good standing. ALPA’s plans are designed by pilots, for pilots, and include disability, critical illness, accident, and loss of license. If you’re worried about the financial impact of a major illness or accident while on a high-deductible health plan, ALPA insurance might be able to help. Depending on the cost of your airline’s health-care plans, you might be able to change to a high-deductible plan and purchase ALPA insurance for a lower total cost than a lower-deductible plan, allowing you to save money while still keeping your peace of mind. Learn more at memberinsurance.alpa.org.